Competitive Authoritarianism

Turkey's Standing on Political Freedoms

Reading time: 4 min

🖊️Paola Testa

Apr 2025

Towards the 2028 Turkish elections: a shift in competitive authoritarianism?

On 19 March 2025, Istanbul mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu (Republican People’s Party, CHP) was detained by Turkish police officers: he now faces accusations of corruption and terrorism abetment. İmamoğlu was considered the most popular presidential candidate to the 2028 Turkish elections – and the major competitor to incumbent president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (Justice and Development Party, AKP). İmamoğlu’s arrest was just one amidst hundreds of harassments, investigations, detainments, and prosecutions against opposition leaders, journalists, lawyers, minorities, and generally speaking, citizens dissenting with the policies adopted by the current government.

Here at YAS, we have analysed the political outlook, the respect for the rule of law, the implementation of political freedoms, and the role of youth in Turkey. These represent the premises on which the case of the current Turkish shift from competitive authoritarianism can be rested. Furthermore, Turkey’s international standing will be forecast in light of the latest domestic and global developments of interest to Ankara.

An overview of Turkey’s political instability

The Republic of Turkey is a presidential republic, meaning that the sitting president does not only serve as the chief of state, but also as the head of government. The president also has the power to appoint the cabinet. In the case of Turkey, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has currently been in office since 2018 and is now serving his second mandate. The next elections are thus scheduled to take place in 2028: the president is elected by an absolute majority of popular votes in a maximum of two rounds and is appointed for a five-year term. All Turkish citizens aged 18 and above may vote. Interestingly, it has not yet been confirmed if President Erdoğan will run to serve a fourth term, which is not at all enshrined in the current Turkish constitution. Erdoğan had previously stated that he would step down at the end of his third mandate. Still, a constitutional amendment has been hinted at by the current coalition government: if passed, that would enable the sitting president to run again for office.

In the early 2000s, political scientists Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way had coined the concept of competitive authoritarianism, of which Turkey has been a rampant example for the last fifteen years. Indeed, a competitive authoritarian regime presents more democratic features than any traditionally authoritarian counterpart. Nonetheless, competitive authoritarianism still does not fall under the umbrella of a fully functioning democracy.

From 2018 onwards, Ankara has undergone extensive policy and constitutional changes, aligning it further to a fully-fledged autocracy. Expert Nate Schenkkan argues that this governance shift may also be explanatory of the peace process launched by the parliamentary majority with the Kurdistan’s Worker Party (PKK). The bargaining chip may be the PKK’s support on the controversial constitutional amendment in exchange for the freedom of Kurdish political leader Abdullah Öcalan (who even called for the dissolution of the PKK in his first open letter in years) and of pro-Kurdish left-wing politician Selahattin Demirtaş, co-leader of the People’s Democratic Party (HDP). Regardless of whether Erdoğan decides to run for president again or the AKP chooses to back up another candidate, this would leave the CHP standing as the government’s main opposition party in the Grand National Assembly (GNA), the legislative branch of Turkey. İmamoğlu’s arrest may hence be exploited to keep his party busy for a while.

The political freedom and youth issues in Turkey

The fact that political freedoms are formally guaranteed in the Turkish constitution further testifies to the competitive authoritarianism adopted by Ankara’s regime. Nonetheless, in practice, violations are systematically reported throughout the country, especially during or in preparation to elections. For instance, religious and ethnic minorities – such as Alevis, Christians, and Kurds –, though formally protected, are repeatedly harassed, discriminated, and persecuted.

Also, police operators often crack down on political opposition gatherings, concerts, celebrations, parades, rallies, and demonstrations – this even happened during Women’s Day celebrations and Pride parades. Civil society groups, NGOs, human rights defenders, LGBTQ+ individuals, women, and even university students are frequently arrested due to dissenting or non-conforming opinions. A similar situation is currently being witnessed during the anti-government protests triggered by İmamoğlu’s arrest: the government has ordered demonstration crackdowns, independent media broadcast disruption, arbitrary detention of individuals, and transportation blockades.

Ankara lacks transparency and accountability due to the 2018 sweeping reforms which allowed the centralisation of power in the hands of the president and due to its increasingly autocratic governing methods. This has led to state control over mainstream media and the press. Subsequently, independent broadcasts, radios, and newspapers are often silenced or shut down: this was the case of Açık Radyo in July 2024. Likewise, freedom on the net is also compromised by obstacles to access, limits on content, and violations of user rights. Social media and websites may be blocked, censorship and pro-government commentators promoted, and individuals may be arrested due to their online activity.

What future for Turkey?

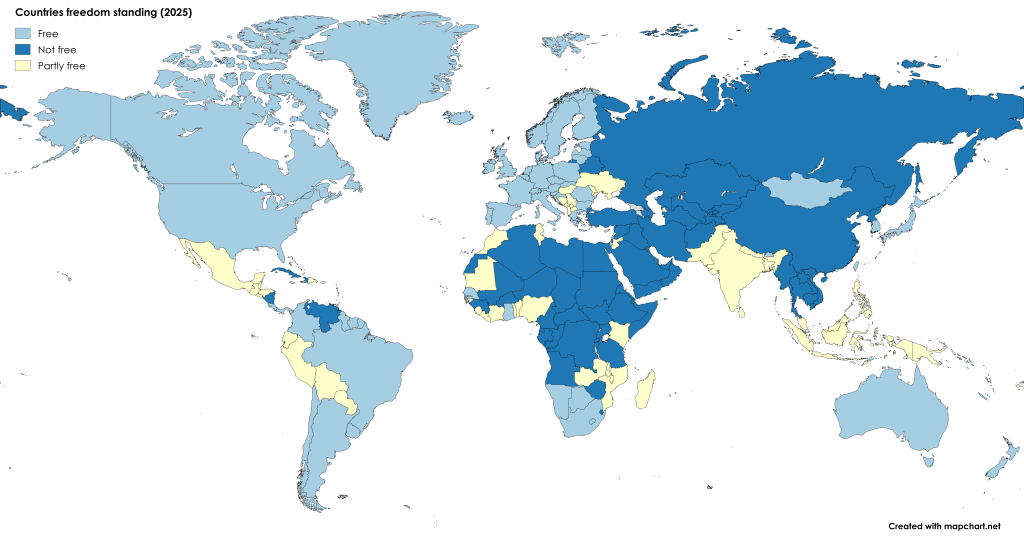

In 2025, Freedom House ranked Turkey as “not free”: Ankara scored 33/100 points for global freedom (divided between 17/40 for political rights and 16/60 for civil liberties) and 31/100 points for Internet freedom (split in 14/25 for obstacles to access, 10/35 for limits on content, and 7/40 for violations of user rights). Turkey positions itself alongside countries such as China, Russia, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Libya, Algeria, and Venezuela – just to name a few –, which were also classified as “not free”. According to Freedom House, this attests to a particularly alarming phenomenon, which has been shaping global governance and the rule of law for the past two decades: countries experiencing freedom declines have outnumbered those with freedom-related gains. In 2024, freedom declines affected as much as 40% of the global population.

In the specific case of Turkey, having a look at the demographics of the country may help understand whom the freedom declines will impact the most. In comparison to many European and Eurasian countries, Turkey can boast a young and dynamic population, with a median age of 34 years. Today, youth aged between 10 and 20 years old may make up more than 20% of the Turkish population – and just by themselves, young people aged 10 – 30 constitute at least 40% of Turkish society. Furthermore, half of the total Turkish population is made up by women. A progressive autocratic policy shift is hence bound to affect youth and women and girls the hardest – also given that these groups are the most underrepresented in positions of power and in politics at the national level. As percentages cannot bear witness to the number of LGBTQ+ individuals, seeing the history of crackdowns on LGBTQ+ manifestations and discrimination on same-sex couples, it is safe to imply that they too will be largely affected by the implementation of more authoritarian policies.

If the AKP or any other far-right and nationalist party gains the upper hand in the 2028 elections, the future will not look bright for Turkey in terms of democracy and the upkeep of political freedoms. As Ankara fights to keep abreast of the new multipolar order, its profit-oriented rule may lead to a wider gap with EU policies and values. As EU access negotiations stall further, Ankara may take up an invitation to join the BRICS and grow both politically and commercially closer to other authoritarian countries – namely Brazil, China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia, among others. In turn, this may be reflected in internal governance choices, making democracy nothing more than a faraway, secondhand dream for today’s youth and for future generations.